Septempber 20, 2021

Kimberly O’Dell

Before Alabama became a state in 1819, it was part of the Mississippi Territory. The land was populated primarily by Native American tribes including the Cherokee, Creek, and Choctaw among others. By 1812, the United States was on the verge of war again with Britain, less than thirty years from the end of the American Revolution. At the same time the U.S. Government was facing dissatisfied and even hostile natives on the borders. The War of 1812, or the 2nd War of Independence, was fought simultaneously with the Creek War and numerous battles were on land that eventually became part of the State of Alabama. The United States was still a young country and ill-prepared to fight a war on its homeland in 1812 let alone against a power of Great Britain’s stature. Most of the men fighting in the wars were militia members called up from each state.

So how did the Mississippi Territory become part of the War of 1812 and the Creek War of 1813-14? After the American Revolution, settlers in Georgia wanted to move West. The Creeks, or Muskogee, were living in the territory and were not happy with the idea of settlers encroaching on their lands. The Creek Nation was divided into two distinct cultural groups: Upper Creeks in the Mississippi Territory, and Lower Creeks in Western Georgia. The Upper Creeks were found primarily near the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers and known to vehemently oppose assimilation pushed on them by the U.S. Government. In Fall 1811, Shawnee warrior Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa (“The Prophet”) came down from the Ohio Valley to forge an alliance between southern tribes and prevent the U.S. settlers from continuing into native territories.

So how did the Mississippi Territory become part of the War of 1812 and the Creek War of 1813-14? After the American Revolution, settlers in Georgia wanted to move West. The Creeks, or Muskogee, were living in the territory and were not happy with the idea of settlers encroaching on their lands. The Creek Nation was divided into two distinct cultural groups: Upper Creeks in the Mississippi Territory, and Lower Creeks in Western Georgia. The Upper Creeks were found primarily near the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers and known to vehemently oppose assimilation pushed on them by the U.S. Government. In Fall 1811, Shawnee warrior Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa (“The Prophet”) came down from the Ohio Valley to forge an alliance between southern tribes and prevent the U.S. settlers from continuing into native territories.

Tecumseh’s message resonated with a section of Creeks know as Red Sticks who opposed assimilation. The White Sticks were a faction of Creeks who favored assimilation and to co-exist with settlers in their territories. The conflict of ideas between the two Creek groups led to The Creek War of 1813-14. Civil war between the Creek factions broke out in the summer of 1813. There had been skirmishes between the area’s militia men and the Red Sticks but the war was initiated by the Fort Mims (modern-day Stockton, AL) Massacre in August of 1813. Over a thousand Red Stick warriors massacred all the inhabitants of the fort due to the carelessness of the settlers leaving the gate open and unguarded.

Tennessee Governor William Blount was requested to raise militia men from both eastern and western Tennessee to attend to the “Creek Problem”. Governor Blount’s state-militia commander General Andrew Jackson raised volunteers quickly since he had already led the state militia to fight in the larger conflict, The War of 1812. Jackson ordered Colonel John Coffee to lead the 2ndRegiment of Volunteer Mounted Riflemen south from Nashville in September 1813. This regiment continued to move south until they reached the Coosa River in the Mississippi Territory. Some of Jackson’s men stopped to camp at modern-day Jacksonville, Alabama. Those men would eventually return and settle the area after Alabama became a state.

Jackson selected a location on the Coosa near Ten Islands to construct a camp in November 1813. The encampment was named Fort Strother, for John Strother (c. 1765-1815) Jackson’s topographical engineer, adviser, and scout. The fort, built in a rectangular shape, was used as a forward supply base and operations center for Jackson during the Creek War. A stockade was added later. While the fort was being constructed, Jackson learned there was a Creek village, Tallushatchee, about fifteen miles from Fort Strother that was harboring Red Stick Warriors.

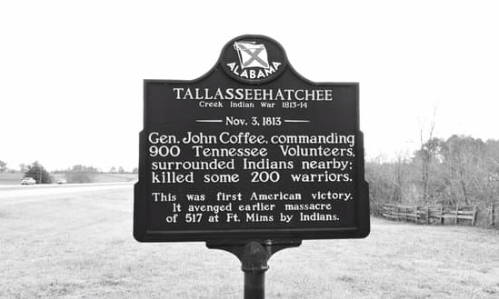

On November 3, 1813, General Jackson ordered Colonel Coffee to take approximately 1000 cavalry men and attack the village of Tallushatchee. Coffee and his men surrounded the village then Coffee sent two columns of militia into the village to draw out the warriors. The warriors rushed the calvary but were almost immediately forced to retreat into village buildings. The 2nd Regiment horsemen tightened the circle then set the buildings on fire. Red Stick casualty numbers vary but the most accepted is 186 warriors killed and 80 women and children taken prisoner. The women and children were relocated to Huntsville to be held there. The militia casualties numbered about 50 and the wounded were taken back to Fort Strother. It was after this battle, that General Jackson found a small infant in his mother’s dead arms on the battlefield and with no relatives remaining he took custody of the child. Jackson and his wife Rachel named the baby Lincoyer and raised the child as their own in Nashville. Sadly, Lincoyer died of tuberculosis at age 16.

While several villages surrender after the Battle of Tallushatchee, this was not the end of the Creek War. There were battles at Talladega/Fort Leslie and Hillabee, along with The Georgia and Mississippi Campaign battles. The final end to the Creek War came at Horseshoe Bend in 1814. Some of the frontiersmen that fought in the battles with Jackson included Davy Crockett and Sam Houston.

At the height of the Creek War, approximately 5000 men were stationed at Fort Strother. In 1815, the fort was the site of a mutiny of troops led by John Strother, cousin of Jackson’s topographical engineer. After 1815, the fort has no mention and the only evidence left is unmarked cemetery. After the war, the Creeks returned to the area and settled in another village closer to modern-day Jacksonville. They chose to name the village Tallushatchee.

No physical structures remain from the battle and the military fort. St. Clair County owns the land that was the site of Fort Strother but the battle field remains largely on private property. A historical marker for Fort Strother is located on AL HWY 144 near Ragland. There are two markers for the battle site: McCullars Lane near Route 73 and HWY 431 just north of the 144 Junction. Multiple efforts have been made through the years to preserve the areas but sadly have come to nothing. The most recent effort was made by late Calhoun County Commissioner Eli Henderson.

NOTE: There are multiple spellings for the battle and village name. For the purposes of this article the spelling Tallushatchee will be used.

Sources:

Blackmon, Richard (2014). The Creek War 1813-1814 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 9780160925429. CMH Pub 74-4. Retrieved September 9, 2021 from https://history.army.mil/html/books/074/74-4/CMH_Pub_74-4.pdf

Kanon, Tom (n.d.). Regimental histories of Tennessee units during the War of 1812. Nashville, TN: Tennessee State Library and Archives. Retrieved September 9, 2021 from https://sos.tn.gov/products/tsla/regimental-histories-tennessee-units-during-war-1812

Smith, Jerry, C. (2013). Pieces of history. Retrieved September 9, 2021 from https://discoverstclair.com/st-clair-history/pieces-of-history/

Kimberly O’Dell is a local historian based in Calhoun County, Alabama. She is the author of Calhoun County (1998), Anniston (2000) and Anniston Revisited (2015) part of the Arcadia Publishing Images of America Series. Website: http://kimberlyodellauthor.wixsite.com/kimberlyodellauthor

Kimberly O’Dell is a local historian based in Calhoun County, Alabama. She is the author of Calhoun County (1998), Anniston (2000) and Anniston Revisited (2015) part of the Arcadia Publishing Images of America Series. Website: http://kimberlyodellauthor.wixsite.com/kimberlyodellauthor

Advertisement